For the last decade, the architecture of state-of-the-art recommender systems has been a story of two models: the Two-Tower for efficient retrieval and the Deep Learning Recommendation Model (DLRM) for powerful, feature-based ranking. This paradigm was stable, effective, and scaled to billions of users.

Now, that era is giving way to a new one.

Sparked by a wave of research, including Meta’s influential “Generative Recommenders” paper, the industry is rapidly shifting towards a new paradigm: treating user behavior as a language. This isn’t just an incremental improvement; it’s a fundamental change in how we represent user intent and build our systems.

This post is a deep dive into this new world. We will deconstruct the modeling techniques that make this possible, and then map out the new set of engineering challenges that teams face when taking these powerful models to production.

The New Paradigm: Modeling Behavior As Language

The core idea is to move away from summarizing a user’s history in a fixed-size feature vector and instead to model the raw, ordered sequence of their recent interactions.

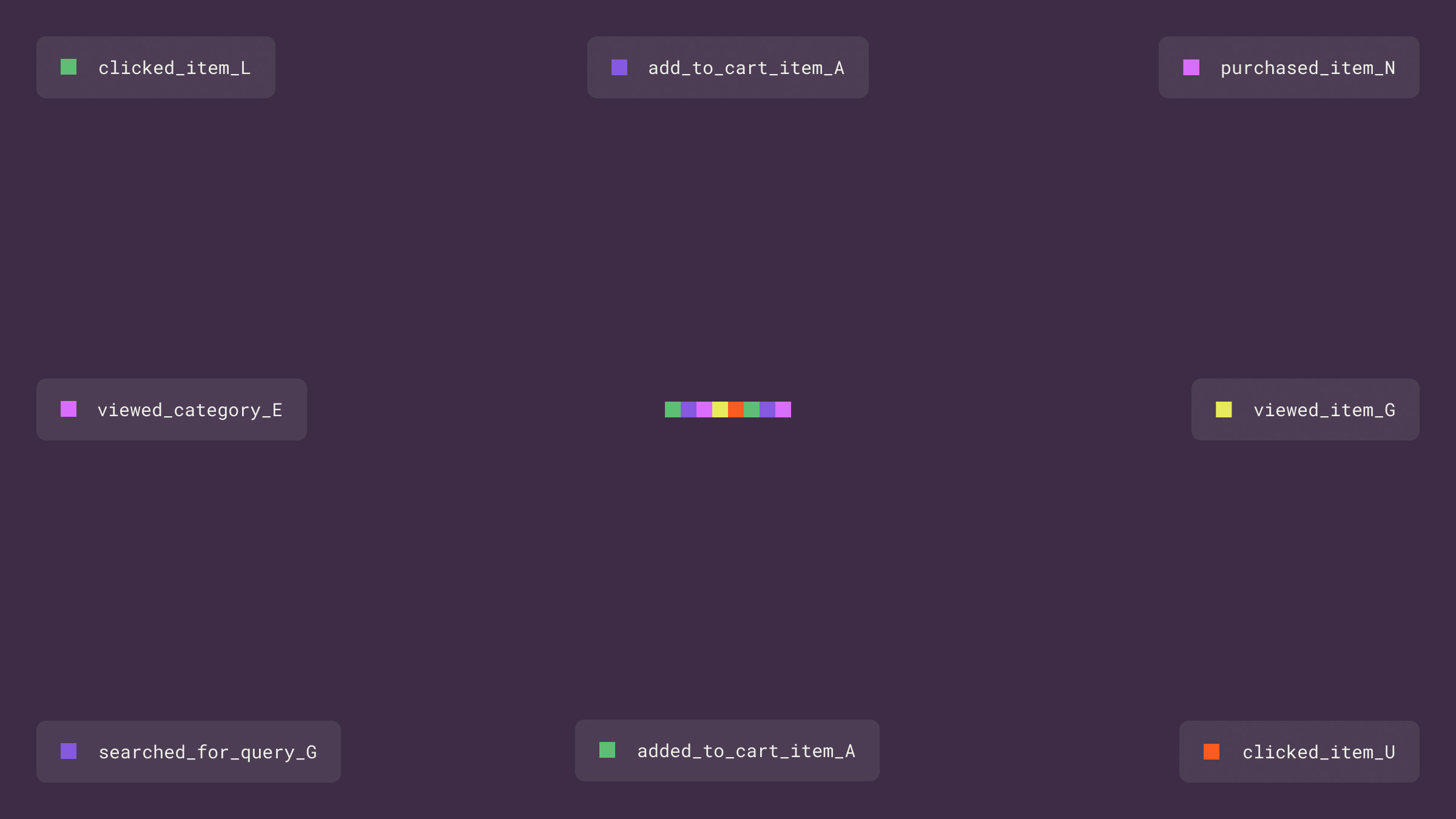

A user’s history, like [viewed_item_A, clicked_item_B, purchased_item_B, ...], is treated like a sentence. The model, typically a Transformer, learns the “grammar” and “vocabulary” of that user’s behavior to predict the next “word”—the next item they are most likely to interact with. This approach, building on a history of research from

N-Grams to SASRec and BERT4Rec, moves the burden of intelligence from the feature pipeline to the model architecture itself.

Deconstructing the Model: From Tokens to Tensors

The Anatomy of a Token: It’s More Than Just an Item ID

While we often simplify the input sequence to a list of item IDs, a production system typically uses a much richer representation for each step. A single “token” or time-step in the sequence is often a concatenation of multiple embeddings.

For a given interaction, this might include:

- The Item’s Semantic ID embedding.

- An Action Type embedding (e.g., view, click, add_to_cart, purchase).

- A Time Delta embedding (representing the time elapsed since the previous action, often bucketized).

- A Dwell Time embedding (representing how long the user spent on the item).

This multi-modal representation allows the Transformer’s attention mechanism to learn far more nuanced patterns, like “the user quickly clicks through several items (low_dwell_time) before making a considered purchase (high_dwell_time) on an item they’ve seen before.”

Handling Content with Semantic IDs

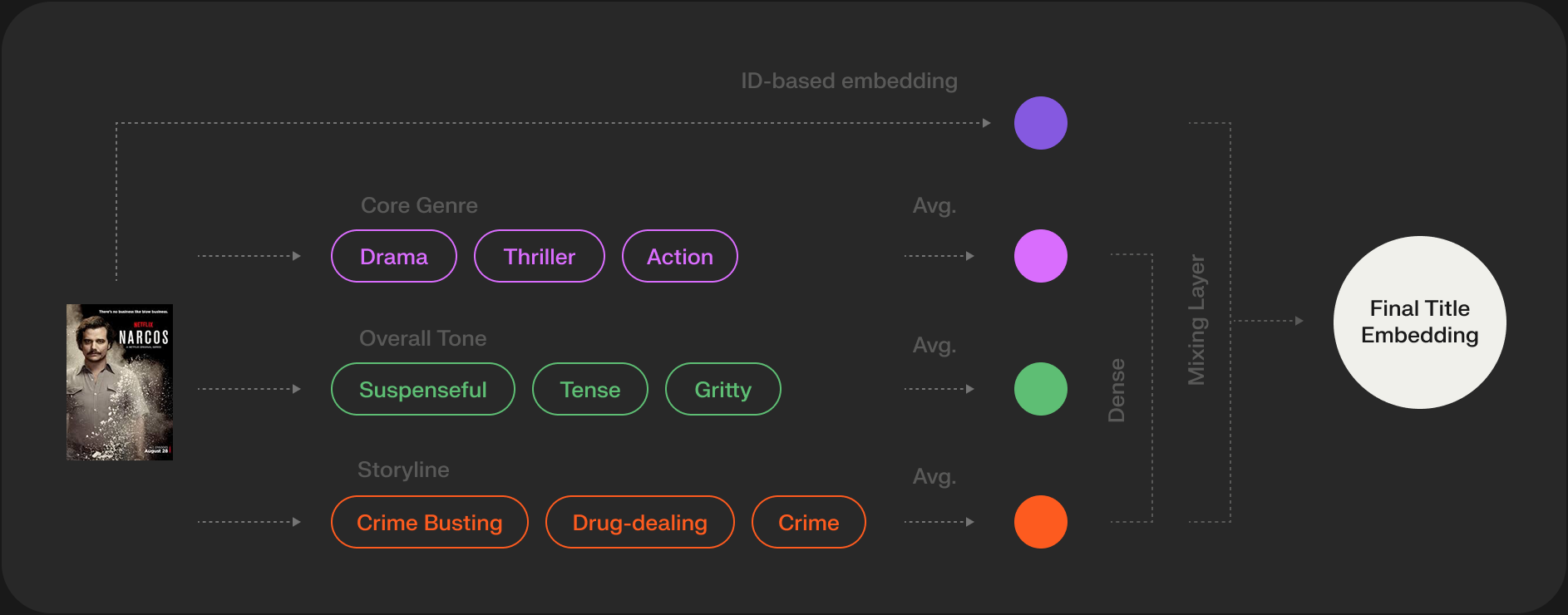

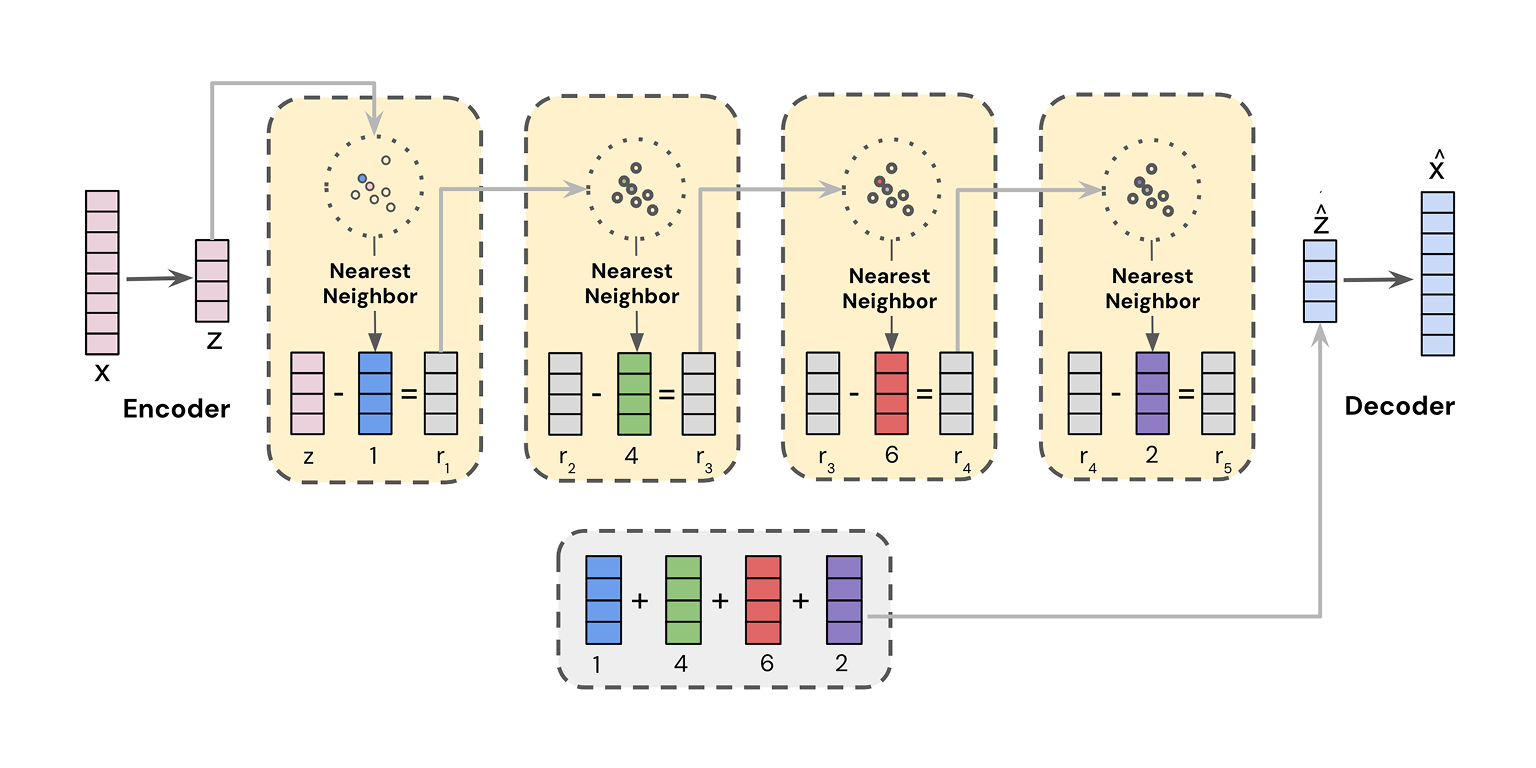

A major challenge is that the “vocabulary” of items is not static. A standard Transformer with a fixed vocabulary can’t handle this. This is where the Semantic ID comes in, a technique detailed in Google’s “Better Generalization with Semantic IDs.”

The process is a two-stage masterpiece:

- Offline Compression: A Residual-Quantized Variational Autoencoder (RQ-VAE) is trained to compress rich, high-dimensional content embeddings into a short, hierarchical sequence of discrete codes (e.g., [1024, 45, 1888, 9]). This sequence is the Semantic ID.

- Online Adaptation: In the ranking model, instead of learning one embedding per item, you learn embeddings for smaller, shared “subwords” of the Semantic ID, often using a SentencePiece Model (SPM).

This provides the best of both worlds: the generalization of content embeddings (solving the item cold-start problem) and the memorization capacity of discrete IDs.

Incorporating Context and Efficiency

The user’s history is not the only signal. The model still needs to understand the real-time context. A common advanced architecture is a dual-stream model. One stream (a Transformer) processes the sequence of user interactions, while a second stream (an MLP) processes request-time features.

But representing actions within the sequence is computationally expensive. Meta’s original approach doubled the sequence length. A brilliant, production-focused solution comes from Meituan’s “Dual-Flow Generative Ranking Network (DFGR).” They use a training-time-only second stream to provide rich action context without the 4x cost penalty of the original approach, making the model significantly more efficient and performant.

The Production Reality: A New Set of Engineering Challenges

Having this powerful model is one thing; running it reliably at scale is another. The architectural shift introduces a new set of production considerations that teams must navigate.

The Central Challenge: Managing Inference Cost and Latency

The O(n²) complexity of self-attention makes real-time inference the primary engineering hurdle. This is a significant departure from the Two-Tower model’s cheap ANN search. The most direct solution is to serve these models on GPUs, often using optimized inference servers like NVIDIA’s Triton.

However, this is an active area of optimization. The trade-off between model size, sequence length, latency, and cost is now a critical consideration. Techniques like knowledge distillation (training a smaller, faster model to mimic a larger one), quantization (using lower-precision arithmetic), and architectural modifications to the attention mechanism are all being actively explored to make these models more efficient and reduce the reliance on expensive hardware.

The Evolving Role of the Feature Store

The traditional feature store, with its focus on serving dozens of aggregated historical features, is changing. Its new, primary role is to serve one thing with extremely low latency: the user’s raw sequence of recent interactions. The online feature store effectively becomes a high-performance “user activity cache” or “session store.” In practice, this is often implemented as a capped list or time-series in a key-value store like Redis or ScyllaDB, which presents its own trade-offs between speed, cost, and durability.

Old Problems in a New Paradigm

While sequential models are incredibly powerful, they are not a silver bullet. Many of the classic, hard problems of recommender systems persist and require dedicated solutions within this new framework.

The most immediate is the user cold-start problem. A sequential model has no history to work with for a new user. This means the system must have a robust fallback strategy. The classic DLRM or a simpler feature-based model doesn’t necessarily go away; it often remains as a crucial component for handling the cold-start journey until enough interactions are gathered to form a meaningful sequence.

Similarly, challenges like managing feedback loops, ensuring fairness, and the offline/online evaluation gap still require careful, dedicated solutions within this new architectural paradigm.

Conclusion

The shift from feature-based models to sequential Transformers represents one of the most significant architectural changes in recommendation systems in years. It’s a paradigm built on the foundational ideas of treating behavior as a language and using content-aware Semantic IDs to manage the vocabulary, and is being rapidly refined for production by the wider research community.

This is not just a simple model swap; it’s a rethinking of our data flow, our hardware, and the very way we represent user intent. The infrastructure challenges are non-trivial, but for teams willing to navigate this transition, the reward is a system that can capture the nuanced, dynamic, and sequential nature of user preferences in a way that was never before possible.

And the frontier is already moving. The next set of challenges will likely involve breaking beyond simple item ID sequences to incorporate multi-modal user histories (sequences of text searches, image views, and product clicks), and solving the problem of long-term memory, moving beyond the 50-100 item session window to build truly lifelong user models. The architectural patterns we’ve discussed here are the foundation upon which that future will be built.

See Shaped in action

Talk to an engineer about your specific use case — search, recommendations, or feed ranking.